“John, you’re wanted in the principal’s office,” Sister Annuciata said to me. I was a high school senior at Central Catholic High School in Reading, Pa., and had never been asked to see Father Leichner. “Is something wrong?” I worried as I walked down a flight of faculty-only stairs to his office.

Father Leichner greeted me with a smile. “I have good news for you, John,” he said. “You’re receiving a scholarship to La Salle College.” He explained that each year La Salle and St. Joseph’s provided the school with four-year scholarships for graduating seniors, and I had been the boy chosen for La Salle.

I knew the scholarship would mean a lot. In Reading, a factory town, my father worked as a bookkeeping clerk in an insurance company; my mother, in addition to caring for my two younger sisters and me, worked as a as a part-time nurse to supplement the family income. My parents wanted to send their oldest child to college, but I knew the expense of it was giving them pause.

I left Father Leichner’s office excited about sharing the good news with my parents later that day. But I was also thinking, “This is thanks to the sign on the bus.”

Fortunately, something had happened in the summer after my freshman year that had changed my life. I was not old enough to get a job and wanted to do more than spend the summer playing back-alley baseball with neighborhood friends. Bored and restless, I was sitting on my front porch one day in early June when I saw a public service message on the side of a bus that was rumbling noisily up the street. I remember the exact words: “Open your mind—read a book.” Such messages had always annoyed me. On general principle I didn’t like being told what I should do. I also resented the implication that my mind was closed just because I didn’t read books and didn’t take school too seriously. I thought to myself, “For the heck of it, I’m going to read a book just so I know for sure it’s a waste of time.”

That afternoon I walked to the one bookstore in town, browsed around, and picked a paperback book—The Swiss Family Robinson—about a family that had been shipwrecked on an island and had to find a way to survive until rescue came. I spent a couple of days reading the story. When I was done, I had to admit that I had enjoyed it and that I was proud of myself for actually having read an entire book.

However, in the perverse frame of mind that was typical of me at the time, I thought, “I just happened to pick out the one story in the bookstore that’s actually interesting. Chances are there aren’t any more.” But the more reasonable part of me wondered, “What if there are other books that won’t waste my time?”

I remembered that upstairs in my closet were some books my aunt had given me but I had never read. I selected Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, a hardbound book so old that its binding cracked when I opened it up. I began reading, and while the activities of Tom were interesting enough, it was his girlfriend Becky Thatcher who soon captured my complete attention. Tom had a friend named Huck Finn, about whom Mark Twain had written another book. So when I finished Tom’s story, I went to the library, got a library card, and checked out The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. I figured this book might tell me more about Becky. As it turned out, it didn’t, but by pure chance I ended up reading one of the great novels of American literature.

By the time I finished Huck’s story, I knew that books could be a source of pleasure, and I sensed also that they could be a source of power. I continued reading for the rest of the summer, and when I returned to school in the fall, I had become a serious student and began focusing on my grades. If it’s true that, as William Butler Yeats said, “Education is not the filling of a pail but the lighting of a fire,” the sign on the bus had lit my fire.

So the principal’s scholarship got this lower-middle-class Irish boy from a factory town into La Salle. That in itself could have been enough reason for me to decide, all these years later, to give back. But an even more compelling reason came into play—five extraordinary professors I had while an English major at La Salle.

Charles V. Kelly (1915–1988)

My first English professor at La Salle was Charles V. Kelly, a former officer in the military and a commanding presence in my freshman composition class. With his stylish clothes, upright posture, assured yet friendly manner, and unlimited energy —even when he was sitting at his front desk, his legs kept moving—he treated us like gentlemen, and we were careful to behave like gentlemen. A serious teacher, he occasionally took a short break to tell us engaging stories about, for example, a first cousin who had been an awkward teenager; we all knew he was referring to the elegant Grace.

My first English professor at La Salle was Charles V. Kelly, a former officer in the military and a commanding presence in my freshman composition class. With his stylish clothes, upright posture, assured yet friendly manner, and unlimited energy —even when he was sitting at his front desk, his legs kept moving—he treated us like gentlemen, and we were careful to behave like gentlemen. A serious teacher, he occasionally took a short break to tell us engaging stories about, for example, a first cousin who had been an awkward teenager; we all knew he was referring to the elegant Grace.

When he returned our first composition assignment, I nervously approached him after class. “Sir, what are all these logs you put in my paper?” I asked—trying to make a joke of the three or four Log’s he had written, along with other comments, in the margins. He looked at me a little wonderingly. “Logic, Mr. Langan, logic,” and went on to explain how I was not thinking clearly.

Years later, in the preface to a composition textbook I published with McGraw-Hill, I paid the following tribute to what Kelly had taught me: “During my first semester in composition, I realized that my teacher repeatedly asked two questions of any paper I wrote: ‘What is your point?’ and ‘What is your support for that point?’ I learned that sound writing consists basically of making a point and then providing evidence to support or develop that point.”

When my book came out, in gratitude I sent Kelly a copy, and he responded with a gracious letter that I’ve kept over all these years. It reads in part:

October 13, 1977

Dear John:

Many thanks for the copy of English Skills and for your very generous compliments to La Salle and its faculty….

When English Skills first crossed my desk, I showed it to John Keenan and together we wondered whether or not its author was ‘our’ John Langan. On the basis of whatever evidence I found at the time—I can’t recall now what it was—we concluded (wrongfully but characteristically, I suppose) that the two were not the same. For one time in my life, I am happy to have been incorrect, especially in view of the success the book has enjoyed and the expanded opportunities it has provided you for writing and publishing….

Sincerely,

Charles V. Kelly

Chairman, English Department

Looking back today, I realize my thanks to Kelly at the time was hardly sufficient: Using the principles of point and support I learned so clearly in his class, I went on after English Skills to author a series of writing and reading books for McGraw-Hill and then my own publishing company, books that I continue to revise and publish to this day

Daniel J. Rodden (1920–1978)

Dan Rodden, my second English professor at La Salle, was a Falstaffian figure who taught a sophomore literature survey. Like Kelly, he encouraged me to consider becoming an English major. I somehow still have one of the papers I did for his class, with its comment “Very good writing—a bit over-much, but that’s a healthy position. You may be kind of a writer.”

Dan Rodden, my second English professor at La Salle, was a Falstaffian figure who taught a sophomore literature survey. Like Kelly, he encouraged me to consider becoming an English major. I somehow still have one of the papers I did for his class, with its comment “Very good writing—a bit over-much, but that’s a healthy position. You may be kind of a writer.”

In my basement recently, I came upon the one La Salle textbook (its cover spine fallen off) that has survived all these years—Interpreting Literature, the everyday teaching text for Rodden’s course. Based on all the underlines and countless margin notes in the book, I see now that we covered most of its 800 pages. Dan’s very first class was unforgettable: he wrote out on the board a definition of art and spent the first week discussing in detail each of the terms: “Art is intellectual recreation through the contemplation of order.”

After that first week, the magic happened. Dan would come in every day, more often than not rolling up his sleeves, and we would open up Interpreting Literature and diligently read and discuss the human themes and values celebrated there, starting with T. S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” and going on to Shakespeare and Thoreau and Ibsen and Thurber and Salinger and Frost and so many more. His method was simple but profound: what does this work tell us about life—what human theme is presented, and what human values are celebrated?

A man of extraordinary energy (at night he ran the school’s acting group, and years later the La Salle theater was to be renamed in his honor), he opened the door of literature for me. If I had to summarize what we learned in those two semesters of discussing biography, fiction, poetry, drama, and essays, it would be in William Faulkner’s Nobel Peace Prize speech—itself one of the works we read in his class: “I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal . . . because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet’s, the writer’s, duty is to write about these things. It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past.”

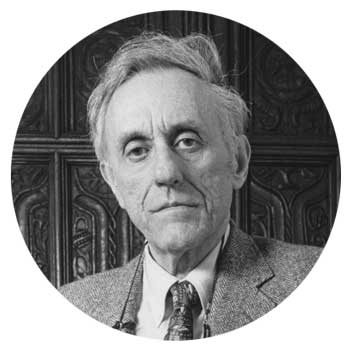

Claude F. Koch (1918–2000)

I had Claude Koch for two courses and his reputation preceded him: Don’t take one of his classes unless you want to work very hard. It was apparent that he himself worked hard. I had heard that he arose two hours early each morning so that he would have time for his creative writing and that he had published poems, stories, and novels. The worn-looking brief case he always carried about on campus bulged with, I imagined, all the student papers he had to read and grade. His eyes often seemed tired, but upon greeting you, they would light up, and his smile was warm and genuine—as if the pleasure of seeing you made anything else irrelevant.

I had Claude Koch for two courses and his reputation preceded him: Don’t take one of his classes unless you want to work very hard. It was apparent that he himself worked hard. I had heard that he arose two hours early each morning so that he would have time for his creative writing and that he had published poems, stories, and novels. The worn-looking brief case he always carried about on campus bulged with, I imagined, all the student papers he had to read and grade. His eyes often seemed tired, but upon greeting you, they would light up, and his smile was warm and genuine—as if the pleasure of seeing you made anything else irrelevant.

A moment that will remain with me forever occurred in the office Koch shared with John Keenan in the now gone Benilde Hall. Koch and I were sitting on a battered leather couch, mid-afternoon sun was flooding from the lone window into the small room, dust motes were floating about, Keenan was squeezed at his desk nearby, and piles of papers and books sat on the floor and every flat surface. In the creative writing course I was taking with Koch, I was indulging at the time in a flowery prose style. I pointed to a turgid passage and asked Koch, “Would you call this a kind of prose-poetry?” And he responded, “I would call this lousy writing.” At the moment he delivered this deserved knockout blow, I heard Keenan draw in a sharp breath and at the same instant do his best to muffle it. It was an indelible teaching moment from a teacher who said exactly the right thing at the right time.

In his course on contemporary poetry, what I remember most is Koch’s expressive reading aloud of poems that left him sometimes overcome by the beauty of the words. Seeing him like that—a man deeply humbled by the beauty of art—made me the more desirous of appreciating that art for myself.

Thanks to Amazon, I was able to order recently one of Koch’s long out-of-print novels, Light in Silence. I went through it, curious as to what it might suggest about the man’s values. I noted the simple, heartfelt dedication, “For my mother and my father,” and then I paged through it to a point near the end where the main character shares his perspective about life: “‘We are inseparable, you know, all of us,’ he said. ‘Like figures from Dante’s hell—our arms around each other’s necks, inseparable forever.’”

John Keenan (1931–2006)

John Keenan, with whom I had a survey course in the novel, was always an everyday guy, rounded and grounded. One could converse with him about almost anything, and he would radiate camaraderie and pleasure and goodness and common sense. In class, he proceeded in a straightforward and workmanlike way, in his wonderful speaking voice, to teach us not just the craft but also the moral vision of The Scarlet Letter and David Copperfield and other novels we discussed. More than anyone I’ve ever known in my life, he would be my candidate as the archetypal decent man.

John Keenan, with whom I had a survey course in the novel, was always an everyday guy, rounded and grounded. One could converse with him about almost anything, and he would radiate camaraderie and pleasure and goodness and common sense. In class, he proceeded in a straightforward and workmanlike way, in his wonderful speaking voice, to teach us not just the craft but also the moral vision of The Scarlet Letter and David Copperfield and other novels we discussed. More than anyone I’ve ever known in my life, he would be my candidate as the archetypal decent man.

I had the good fortune to connect with John a year or two before he died–he was retired but working on notes for an edition of Dubliners that my company planned to publish–and when he visited, he met my wife. As the three of us cordially spoke, he happened to mention how he had played a saxophone in a big band. My wife remarked on that wonderful detail later, saying, “There is great joy in that man.”

Two former students testify in better words than I to Keenan’s specialness. John Rooney, who graduated from La Salle in 1978, recalls in a previous issue of La Salle Magazine what Keenan had said to him about teaching: “Teaching is really related to who one is—as a whole person. It is working with students, being there to talk to students. I’m happy teaching in a place where good teaching is valued—La Salle’s been a good match for me.”

And my nephew Paul Langan, who graduated from La Salle in 1995, shared this memory of Keenan: “I’d often see him in hallways during late afternoons, a man in his mid-70s or so with his tuft of white hair, assisting a colleague to her car after work. John would laugh and converse with her the whole time until she made it safely to her car parked just outside. It was an old-fashioned gentlemanly gesture that happened quietly without fanfare.”

Brother Daniel Burke (1926–2015)

I had Brother Burke for a course in literary criticism as well as for my senior English seminar. A tall, slender man with a Roman collar and black shirt, he was one of my Christian Brother English professors. He had such a calm and quiet manner that you were tempted to lower your voice when speaking to him. A patient, gentle teacher, he helped me see the endless complexity in twentieth-century literature and, by extension, in life. He taught me about form and beauty in a literary work and gave me tools of literary analysis that were to serve me well in graduate school and my own teaching and writing about literature. I still recall his correction of a student who protested loudly that there were too many subtleties in a story under discussion: “Some of us,” Brother Burke softly said, “tread more lightly.”

I had Brother Burke for a course in literary criticism as well as for my senior English seminar. A tall, slender man with a Roman collar and black shirt, he was one of my Christian Brother English professors. He had such a calm and quiet manner that you were tempted to lower your voice when speaking to him. A patient, gentle teacher, he helped me see the endless complexity in twentieth-century literature and, by extension, in life. He taught me about form and beauty in a literary work and gave me tools of literary analysis that were to serve me well in graduate school and my own teaching and writing about literature. I still recall his correction of a student who protested loudly that there were too many subtleties in a story under discussion: “Some of us,” Brother Burke softly said, “tread more lightly.”

My appreciation of Brother Burke deepened when, after his death last year, his obituary described how in 1971 he had been part of a fasting vigil in Washington to protest the Vietnam War as well as racial tensions and poverty in the country. Living on water and juice, he stood outside the White House for seven days. As stated in the Philadelphia Inquirer, Brother Burke said at the time, “If anyone had predicted that I would become involved in a public demonstration, I would have laughed and said that simply wasn’t my style. But the religious nature of this action compelled me to think about my responsibilities in a very personal way.”

With Brother Burke’s death last year, all five of these men are now gone. Thinking back, I loved them all, and I feel a deep sadness at their passing. Like other dedicated professors I had at La Salle, they are testament to the commitment that La Salle made then, and I believe continues to make, to the importance of teaching and humanistic values. If a sign on a bus lit my learning fire, my professors at La Salle provided the fuel.

After La Salle, I earned money for graduate school by working in factory jobs for a couple of years. I then went on to earn an M.A. and with the example set by my memorable La Salle professors became a college teacher myself. In a night class in developmental writing, I met a student named Walter, a young Latino man who worked as a busboy at a restaurant near Atlantic City and whose goal was someday to become a maître d’.

I was stunned by Walter’s intense desire to learn and the level of attention he gave me in class. Still learning how to teach, I had been asked to use a book called Questions of Rhetoric and Usage—a pompous and condescending text written by an author who managed to be a poor writer, thinker, and teacher and who for inexplicable reasons had been permitted to publish a book about writing. I was angry and embarrassed that I was not a better teacher with a better book. At the same time I realized, in a defining moment in my life, that I wanted to help teach students like Walter the skills they needed to advance in their lives.

The principles I learned in Charles Kelly’s composition class at La Salle gave me the foundation I needed to develop materials that Walter would understand. The down-to-earth teaching styles of Dan Rodden and John Keenan provided me with models of how to relate to students. The dedication and values embodied by Claude Koch and Brother Burke—and, in fact, all these men—inspired me to do my best for my students.

I began authoring books that were published by McGraw-Hill about writing and reading skills. The books were well received, and eventually I was able to start my own publishing company. Since then, I have continued to be involved in reading and writing skills education as both an author and publisher. If I had Walter as a student today, I would be ready to do him a bit of justice.

A few years back, an article in La Salle Magazine about the university’s Academic Discovery Program caught my attention. La Salle was searching out motivated, hard-working students from low-income sections of the Philadelphia area and offering 40 or so of them per year a chance to go to college. The program, which supports students through all four years, has an exceptional graduation rate.

Impressed that La Salle made helping others in need part of its mission—just as it had helped me with a principal’s scholarship—I got in touch with the ADP director, Bob Miedel, and arranged to donate books from my publishing company as well as make an annual contribution to the program.

I so admired Bob’s personal commitment to helping underprepared students that I invited him to contribute to a collection of essays my company will publish about beliefs and values. He writes in his piece, “I have been very lucky to find my mission in life which is, in essence, to help others—specifically by helping them earn their college degrees.”

Bob’s words moved me and made me think of my own experience at La Salle—both the scholarship I had received and the impactful and caring professors I had been blessed to have. They embodied a shared good spirit, all working together to educate the young—to, borrowing an image from one of T.S. Eliot’s poems, launch “new ships” into the world.

I was similarly moved when I read, in a recent issue of La Salle Magazine, the words Colleen Hanycz spoke in her inaugural address as the university’s new president. She referenced the inspiring words of the American orator Robert Ingersoll: “We rise by lifting others.” And she reminded us of the visit of Pope Francis to Philadelphia and “his call to each of us to strive for justice by celebrating the dignity of the human person and the advancement of the common good.”

I shared with my wife Bob’s essay and Colleen’s inaugural address and together we discussed my emerging thoughts about what La Salle and its professors had meant to me. Understanding my feelings, she did not hesitate to join me in a decision to contribute to the university and the humanistic ideals at the heart of its mission.

JOHN LANGAN, ’63, AND DR. JUDITH NADELL DONATE $1 MILLION TO SUPPORT UNDERSERVED STUDENTS

John Langan, ’63, and his wife, Dr. Judith Nadell, have created a $1 million endowment to support at-risk first-generation La Salle students who work hard and are motivated to earn a college degree, but who are in need of additional support services and financial assistance.

“We are honored and beyond grateful to receive this generous gift,” said President Colleen M. Hanycz. “The John Langan, ’63 and Dr. Judith Nadell Endowment for Student Success will allow us to provide even more underserved students with a transformative education, which is a direct reflection of our values instilled by the Christian Brothers and the legacy of St. John Baptist de La Salle.”

After graduating from La Salle, Langan taught night classes where he met a young, passionate first-generation student with set career goals and aspirations. “I was stunned by his intense desire to learn. At the same time I realized, in a defining moment in my life, that I wanted to help teach students like him the skills they needed to advance in their lives,” he said.

Langan went on to author and publish a series of reading and writing skills textbooks for McGraw-Hill, and later founded Townsend Press, a New Jersey-based independent publisher of educational materials for students from grade school through college.

Now, even more high-risk students will be provided the resources to help them thrive at La Salle and achieve success beyond college in their professional and personal lives.